The FCC is auctioning off a swath of high band frequencies that carriers can use to deliver 5G. Success on that front might deliver a peculiar benefit for enterprise customers.

Radio spectrum is the raw material of any wireless business, and mobile operators are carrying billions of dollars’ worth of radio licenses on their balance sheets. The reason for this is that long ago mobile operators made the strategic decision to utilize only licensed frequencies to provide their services. The mobile operators justified the cost with the argument that they were selling a service people were paying real money for and, following the precedent of the wired networks that preceded them, the wireless carriers wanted their wireless service to work. One way to help ensure that was to utilize radio channels where there would be no chance of interference from other users sending on their channels.

To be sure, licensed bands provide a very high degree of insurance against unwanted interference, but that insurance comes with a price. The original 800 MHz cellular frequencies were passed out for free, but starting in 1997, the FCC began auctioning off radio spectrum. Since then, the US government has raised over $60 billion, according to Wikipedia. Recent auctions have sold off portions of the low frequency 600 MHz and 700 MHz bands, which are highly prized bands, as the signals travel farther with less signal loss. That translates into a requirement for fewer cell sites and also delivers better building penetration for better indoor coverage. However, there is only so much of “the good stuff” to go around, and user demand for wireless data service appears to be insatiable.

U.S. carriers’ main options to continue to grow their network capacity fall into three categories of bands. The best way to understand the impact of these bands is to look at how they perform:

- Low Band (< 1 GHz): Best option for transmission range and building penetration.

- Mid-Band (1 GHz to 5 GHz): Suitable for either wide area or inbuilding applications.

- High Band/Millimeter Wave (>20 GHz): Range measured in hundreds of meters but suitable for indoor (typically “in room”) and small cell applications.

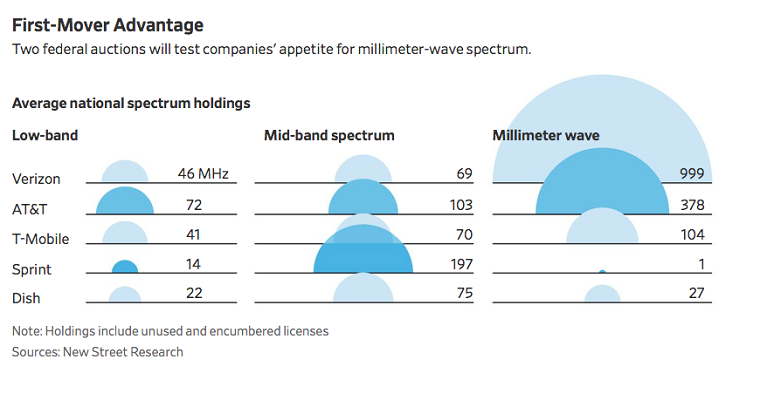

The Wall Street Journal

recently published an article that included an analysis from New Street Research of the frequency holdings by band for the four national cellular carriers and Dish Network.

For enterprise users, our preference would be for the carriers to keep their paws of the 5 GHz U-NII band, as that will inevitably lead to contention (and hence, diminished capacity) for our Wi-Fi networks. The cellular carriers insist that there would be no impact from their use of 5 GHz, but “disingenuous” is our most polite assessment of that position.

Let’s take a look at each of the four major carriers’ holdings and what that might mean for their frequency planning going forward:

- Verizon: Verizon is relatively thin in the low band, and it will need to focus its available holdings in the macro network. Its mid-band (primarily 1.9 GHz PCS spectrum) is substantial, but it is riding high in high-band thanks to its 2017 acquisition of Straight Path Communications that brought with it extensive licenses in the 28 GHz and 39 GHz bands. Of course, Verizon has also been very active in LTE-Unlicensed so it will have two choices for how it can address small cell requirements. There has been little real-world experience with millimeter wave in commercial deployments, but for the sake of our Wi-Fi networks, we really hope it works out.

- AT&T: AT&T has respectable holdings across all bands and is particularly strong in the valuable low bands. Like Verizon, it also has a decent position in the high band, but it’s important to note that greater signal loss also degrades signal-to-noise (S/N) ratio, which in turn reduces bandwidth efficiency, so you’re not getting as many bits per second on a cycle of high band as you do on a cycle of mid- or low-band spectrum.

- T-Mobile: T-Mobile has recently beefed up in the low band, spending close to $8 billion in the 600 MHz auctions, putting it in a solid position there. It also holds a decent position in the mid-band, but with little high-band spectrum available, we’re probably looking at the need to bolster its mid-band with 5 GHz U-NII for small cell deployments.

- Sprint: Sprint’s spectrum profile is vastly different from the others. It has a pittance in the low band, less in the high band, but is mad fat in the mid-band with almost 200MHz. That mid-band is made up of the 1.9 GHz it used for its CDMA network, plus a major hunk in the 2.5 GHz band (aka “Band 41”) it got with the acquisition of Nextel in 2004; the Nextel acquisition also accounts for the sliver Sprint has in the 800 MHz band. Buying Nextel may have been the worst business decision Sprint has ever made, but it has left the company with a major hunk of spectrum it can use for either macro network or small cell applications. It also means Sprint probably has little need to horn in on our 5 GHz Wi-Fi spectrum. Needless to say, a combination of Sprint and T-Mobile would offer a real alternative to the majors.

Most enterprise customers have zero understanding of frequency spectrum or its impact, but it’s probably time they started looking at this issue strategically. Wi-Fi is a strategic infrastructure asset, and one in which enterprises have invested billions of dollars. The utility of that investment could now be in jeopardy.

The cellular carriers are working to sell their “No problem” story for the use of unlicensed spectrum in their networks, but you should consider the actual meaning as “No problem for me!” The reality going forward is that indoor cellular coverage is a persistent problem, and with the advent of 5G, millimeter wave, and small cells, this could turn into a gargantuan mess. And if you think that your existing distributed antenna system (DAS) is going to save your bacon, think again.

The big message for IT coming out of this, is that it’s time to get involved. In many organizations, cellular services are managed primarily by the purchasing department, where the only “frequency” they deal with involves coffee breaks. We all know users want to communicate wirelessly wherever they are, but inattention by IT in this area can leave organizations ill-prepared to deliver on the mobility promise.